Monday, October 30, 2006

What we can learn from New Jersey

Friday, October 27, 2006

"Super Secret" Teacher Blogs

Greetings from New Mexico! I've been thinking about an idea that needs researching, and might be of interest to you. I've kept up with your blog ever since leaving Purdue since I find the ideas you post rather interesting, and it helps me feel connected to my former institution.

Anyway, one of my students mentioned to me not too long ago that she kept a "super-secret blog" during her first (and only) year of teaching. She sounded so embittered that I couldn't resist doing a little investigation, and I turned up with her blog here: http://sagacious-teacher.blogspot.com/. You can almost see the desperation and helplessness she feels as she navigates her year that involves teaching with few resources, unexpected politics with administration, difficult kids, etc. (incidentally, she taught in a rural town that is one town over from the one where I grew up; the similarities are uncanny). In her blog, she references another similar blog: http://hategrade.blogspot.com/2006/05/respite.html.

Anyway, it strikes me that through these "Super Secret" blogs, we are gaining a window in the successes, failures, strategies, theories, and coping mechanisms of teachers (drinking, smoking, and cursing included). I would love to scour the web for more of these teacher blogs - it's rich data!

Unfortunately, it doesn't fit in my "Research Scheme." But it might fit in yours (or perhaps one of your students...?). If nothing else, it might make for some rich classroom discussion!

Hope you are well. It's seventy degrees here, and I now live in a swing state, so I have little to complain about. ;)

"Super Secret" Teacher Blogs

Greetings from New Mexico! I've been thinking about an idea that needs researching, and might be of interest to you. I've kept up with your blog ever since leaving Purdue since I find the ideas you post rather interesting, and it helps me feel connected to my former institution.

Anyway, one of my students mentioned to me not too long ago that she kept a "super-secret blog" during her first (and only) year of teaching. She sounded so embittered that I couldn't resist doing a little investigation, and I turned up with her blog here: http://sagacious-teacher.blogspot.com/. You can almost see the desperation and helplessness she feels as she navigates her year that involves teaching with few resources, unexpected politics with administration, difficult kids, etc. (incidentally, she taught in a rural town that is one town over from the one where I grew up; the similarities are uncanny). In her blog, she references another similar blog: http://hategrade.blogspot.com/2006/05/respite.html.

Anyway, it strikes me that through these "Super Secret" blogs, we are gaining a window in the successes, failures, strategies, theories, and coping mechanisms of teachers (drinking, smoking, and cursing included). I would love to scour the web for more of these teacher blogs - it's rich data!

Unfortunately, it doesn't fit in my "Research Scheme." But it might fit in yours (or perhaps one of your students...?). If nothing else, it might make for some rich classroom discussion!

Hope you are well. It's seventy degrees here, and I now live in a swing state, so I have little to complain about. ;)

Thursday, October 26, 2006

Declining Number of Foundations Scholars

Total number choosing “social/philosophical foundations of education”-

1960-64 -- 312

1965-69 -- 1188

1970-74 -- 1430

1975-79 -- 1197

1980-84 -- 930

1985-89 -- 605

1990-94 -- 545

1995-99 -- 647

TOTAL (1960-1999) -- 6854

yearly average for those choosing “social/philosophical foundations of education”-

1960-64 -- 62

1965-69 -- 238

1970-74 -- 286

1975-79 -- 239

1980-84 -- 186

1985-89 -- 121

1990-94 -- 109

1995-99 -- 129

TOTAL (1960-1999) -- 171

So what the numbers clearly show is a decline from 250 or so foundations scholars coming out each and every year throughout the 1960s and 1970s to about 150 or so foundations scholars coming out each and every year beginning in the 1980s. I checked the most recent (2001 through 2004) SED data and the numbers are more or less the same, in the low 100s. So two issues immediately pop out for me: first, that there is a quantifiable and drastic decline in the number of foundations scholars being produced each year; second, where are all of these scholars going?? There are nowhere near that number of foundations-type jobs out there. So do they go into teacher education? Curriculum and instruction? Educational leadership? Sounds like a good research project for somebody.

Declining Number of Foundations Scholars

Total number choosing “social/philosophical foundations of education”-

1960-64 -- 312

1965-69 -- 1188

1970-74 -- 1430

1975-79 -- 1197

1980-84 -- 930

1985-89 -- 605

1990-94 -- 545

1995-99 -- 647

TOTAL (1960-1999) -- 6854

yearly average for those choosing “social/philosophical foundations of education”-

1960-64 -- 62

1965-69 -- 238

1970-74 -- 286

1975-79 -- 239

1980-84 -- 186

1985-89 -- 121

1990-94 -- 109

1995-99 -- 129

TOTAL (1960-1999) -- 171

So what the numbers clearly show is a decline from 250 or so foundations scholars coming out each and every year throughout the 1960s and 1970s to about 150 or so foundations scholars coming out each and every year beginning in the 1980s. I checked the most recent (2001 through 2004) SED data and the numbers are more or less the same, in the low 100s. So two issues immediately pop out for me: first, that there is a quantifiable and drastic decline in the number of foundations scholars being produced each year; second, where are all of these scholars going?? There are nowhere near that number of foundations-type jobs out there. So do they go into teacher education? Curriculum and instruction? Educational leadership? Sounds like a good research project for somebody.

Wednesday, October 25, 2006

NCLB - Pigskin Version

NO CHILD LEFT BEHIND---The Football Version

1. All teams must make the state playoffs and all MUST win the championship.

If a team does not win the championship, they will be on probation until

they are the champions, and coaches will be held accountable. If after two

years they have not won the championship their footballs and equipment will

be taken away UNTIL they do win the championship.

2. All kids will be expected to have the same football skills at the same time

even if they do not have the same conditions or opportunities to practice on

their own. NO exceptions will be made for lack of interest in football, a

desire to perform athletically, or genetic abilities or

disabilities of themselves or their parents. ALL KIDS WILL PLAY FOOTBALL AT A PROFICIENT LEVEL!

3. Talented players will be asked to workout on their own, without

instruction. This is because the coaches will be using all their

instructional time with the athletes who aren't interested in football, have

limited athletic ability or whose parents don't like football.

4. Games will be played year round, but statistics will only be kept in the

4th, 8th, and 11th game. It will create a New Age of Sports where every

school is expected to have the same level of talent and all teams will reach

the same minimum goals. If no child gets ahead, then no child gets left behind.

If parents do not like this new law, they are encouraged to vote for vouchers

and support private schools that can screen out the non-athletes and prevent

their children from having to go to school with bad football players.

NCLB - Pigskin Version

NO CHILD LEFT BEHIND---The Football Version

1. All teams must make the state playoffs and all MUST win the championship.

If a team does not win the championship, they will be on probation until

they are the champions, and coaches will be held accountable. If after two

years they have not won the championship their footballs and equipment will

be taken away UNTIL they do win the championship.

2. All kids will be expected to have the same football skills at the same time

even if they do not have the same conditions or opportunities to practice on

their own. NO exceptions will be made for lack of interest in football, a

desire to perform athletically, or genetic abilities or

disabilities of themselves or their parents. ALL KIDS WILL PLAY FOOTBALL AT A PROFICIENT LEVEL!

3. Talented players will be asked to workout on their own, without

instruction. This is because the coaches will be using all their

instructional time with the athletes who aren't interested in football, have

limited athletic ability or whose parents don't like football.

4. Games will be played year round, but statistics will only be kept in the

4th, 8th, and 11th game. It will create a New Age of Sports where every

school is expected to have the same level of talent and all teams will reach

the same minimum goals. If no child gets ahead, then no child gets left behind.

If parents do not like this new law, they are encouraged to vote for vouchers

and support private schools that can screen out the non-athletes and prevent

their children from having to go to school with bad football players.

Tuesday, October 24, 2006

I take comfort in knowing that there are adults that know less history than I do

That MLK Jr. freed the slaves is, apparently, a very common misconception. Why? Chris says: "it shows how poor the teaching on race issues is. Teachers don't really talk about race in the present, and it creates major problems for talking about the past."

I think that's probably true, but I think there's also a simpler explanation. I was watching my tivoed episode of Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip tonight, and at some point two of the main characters go out to see a black stand-up comedian. They think he's so funny and smart that they hire him on the spot as a writer. Here's an approximate paraphrase of one of his jokes:

"I think about African American slaves, and about how we stacked up against other slaves. Look at the pyramids -- those were built by slaves. No one ever told us we could use geometry!What????

And those slaves, they got Moses. Now, I'm a big fan of the Emancipation Proclamation and all. But they got a burning bush. We got a memo: 'Free at last, free at last, thank God Almighty, we are free at last.'"

This coming from what's supposed to be the pinnacle of network TV show writing. If they think MLK freed the slaves, what chance is there for my kids?

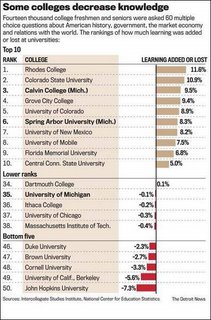

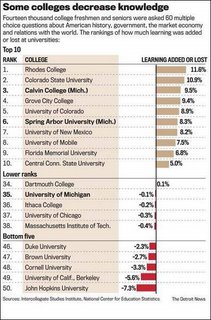

The New Un-American Activities Committee

It is called the National Civic Literacy Board. It is packed with right-wing conservatives, and its intent is the purging of American universities. Check out the negative learning going on, according to the "research findings" shown in the chart at left (click it to enlarge). Is there any doubt which universities are in the cross-hairs?

It is called the National Civic Literacy Board. It is packed with right-wing conservatives, and its intent is the purging of American universities. Check out the negative learning going on, according to the "research findings" shown in the chart at left (click it to enlarge). Is there any doubt which universities are in the cross-hairs?The commentary below by John Seery is from Huffington Post:

Watch out. The conservative assault on our nation's colleges and universities continues.

We've seen David Horowitz's book warning about "dangerous" professors and his clumsy Academic Bill of Rights campaign. We've seen Sec. of Education Margaret Spellings' report on the Future of Higher Education and its proposal to submit our 6000 autonomous colleges and universities to strict federalization.

And now, last week, we received a report--"The Coming Crisis in Citizenship"--from the Intercollegiate Studies Institute's National Civic Literacy Board, which claims to prove that our colleges and universities (read: those bastions of liberalism) are failing to deliver a proper Preparation for Citizenship to our nation's young adults, and may even be corrosive to our American way of life.

The ISI-funded study was based on a multiple-choice examination given to 14,000 college freshman and seniors to assess their factual knowledge in four areas: American History, U.S. Government, America and the World, and the Market Economy. The National Civic Literacy Board assigned an "F" grade to college students in all categories. The Board emphasized that college seniors barely knew anything more about such matters than incoming frosh. And it emphasized that many of the most prestigious schools and most costly schools (read: most liberal schools) produced the worst overall scores, and it singled out Brown University, Georgetown University, and Yale University as places where "negative learning" seems to transpire between incoming and outgoing students. Finally, somehow on the basis of this multiple-choice examination, the Board claims to "prove" that students who have "demonstrated greater learning of America's history and institutions were more engaged in citizenship activities such as voting, volunteer community service, and political campaigns."

So what's going on here?

It just so happens that I attended a conference on civic education last week at Georgetown University. It just so happens that the ISI apparently helped fund that conference (unbeknownst to me beforehand). It just so happens that in my own talk at the conference I severely criticized the findings of the National Civic Literacy Board. I pointed out, for instance, that Stanford Professor of Education and History Sam Wineburg, in his award-winning book, Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts, and in subsequent studies had already demolished the scholarly credibility of a fact-based diagnostic as a way of teaching and understanding American history. Moreover, the premise that you are a "better" citizen and will be more "engaged" because you can identify Yorktown as the battle that brought the American Revolution to an end is just silly.

After my talk, a tall gentleman came up to me and introduced himself: Lt. General Josiah Bunting III, President of the National Civic Literacy Board. Oops! He was eminently gracious, I must say. We exchanged a few polite words. And then I heard him deliver his own address to a lunchtime audience. Most of it was about the virtues of a proper university education, all very above board. But toward the end of his remarks Lt. General Bunting showed more of his own cards. He lamented the presence of so many liberal faculty members in U.S. colleges and universities today, and he concluded his talk thus: "This must change."

I did some Googling. Turns out that the National Civic Literacy Board isn't so national after all. It is simply stacked with conservatives. The directors, besides Lt. General Bunting, include a former Reagan administration official, a former George W. Bush administration official, and a retired Rear Admiral who was Director of Naval Intelligence. Board members include U.S. Senator George Allen; the CEO of the Philip M. McKenna Foundation; the CEO of the National Association of Manufacturers; a Senior Fellow from the Hoover Institution; Roger Kimball, Editor of the New Criterion; Robert George, Director of the Madison Program at Princeton; a former Secretary of the Army; a Wall Street Journal Editorial Board member; a retired Vice Admiral in the Navy; an American Enterprise Institute scholar; a former CEO of Household Finance Corporation; and Lewis Lehrman of the Lehrman Institute; and so on. Does the mission of investigating civic literacy really require such a one-sided, unrepresentative, and so obviously politicized panel?

Conservatives are jumping all over the report with glee, and you can bet that they will press hard for the Board's recommendation that these colleges need to be held "accountable" for the way they contribute to the "civic life" of America, or not.

After I started to realize what was going on at the conference, namely that some folks in attendance saw "civic education" as a proxy and euphemistic front for a conservative agenda, I approached Lt. General Bunting with another line of inquiry. I pointed out to him that I, too, sometimes give my own students a pop quiz on American civics and American civic values, but my questions aren't about the particularities of the Civil War or Keynesian economics. Instead, I ask the following:

How many of you believe in constitutional government? How many of you believe in the rule of law? How many of you believe in checks and balances and the separation of powers among different branches of government? How many of you believe in due process? How many of you believe in trial by jury? How many of you believe in contested elections? How many of you believe in a bill of rights that protects freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, etc.? How many of you believe in universal adult suffrage? How many of you believe in the basic equality of all humans, as opposed to a caste system or a system of inherited privileges? How many of you believe that sovereignty resides in the consent of the governed? How many of you believe in democracy, rather than monarchy or aristocracy or dictatorship?

Remarkably in my experience, I've found that my students understand those questions very well and are in lock-step unanimity in endorsing those civic values. They're not the civic dummies that the National Literacy Board is trying to make them out to be.

I heard at the conference several conservative commentators bemoaning the alleged fact many liberal academics refuse to assert the "moral superiority" of the American government over other governments. What I hear in those words is something ominous: the search for an unassailable American patriotism and therewith, the search for a blanket justification for war; and also as part of that campaign, a rearguard search for scapegoats for the current national malaise in our present wartime fiasco--to be attributed no longer to the "liberal media" or to "liberal politicians" or to "liberal judges" but now to "the liberal professoriate." Holding institutions "accountable" will mean promoting American civic virtues as these conservatives define those virtues, while silencing dissenters by other means.

Why didn't the National Civic Literacy Board simply call itself the new Un-American Activities Committee? Wouldn't that have been the more forthright and honest name?

Why won't mainstream media outlets conduct even a modicum of research to inform readers and viewers about the not-so-hidden agenda behind a report such as this, instead of merely reciting uncritically the Board's findings and recommendations? Shouldn't there be some civic education about the American founders' views about the importance of a vigilant Fourth Estate?

The New Un-American Activities Committee

It is called the National Civic Literacy Board. It is packed with right-wing conservatives, and its intent is the purging of American universities. Check out the negative learning going on, according to the "research findings" shown in the chart at left (click it to enlarge). Is there any doubt which universities are in the cross-hairs?

It is called the National Civic Literacy Board. It is packed with right-wing conservatives, and its intent is the purging of American universities. Check out the negative learning going on, according to the "research findings" shown in the chart at left (click it to enlarge). Is there any doubt which universities are in the cross-hairs?The commentary below by John Seery is from Huffington Post:

Watch out. The conservative assault on our nation's colleges and universities continues.

We've seen David Horowitz's book warning about "dangerous" professors and his clumsy Academic Bill of Rights campaign. We've seen Sec. of Education Margaret Spellings' report on the Future of Higher Education and its proposal to submit our 6000 autonomous colleges and universities to strict federalization.

And now, last week, we received a report--"The Coming Crisis in Citizenship"--from the Intercollegiate Studies Institute's National Civic Literacy Board, which claims to prove that our colleges and universities (read: those bastions of liberalism) are failing to deliver a proper Preparation for Citizenship to our nation's young adults, and may even be corrosive to our American way of life.

The ISI-funded study was based on a multiple-choice examination given to 14,000 college freshman and seniors to assess their factual knowledge in four areas: American History, U.S. Government, America and the World, and the Market Economy. The National Civic Literacy Board assigned an "F" grade to college students in all categories. The Board emphasized that college seniors barely knew anything more about such matters than incoming frosh. And it emphasized that many of the most prestigious schools and most costly schools (read: most liberal schools) produced the worst overall scores, and it singled out Brown University, Georgetown University, and Yale University as places where "negative learning" seems to transpire between incoming and outgoing students. Finally, somehow on the basis of this multiple-choice examination, the Board claims to "prove" that students who have "demonstrated greater learning of America's history and institutions were more engaged in citizenship activities such as voting, volunteer community service, and political campaigns."

So what's going on here?

It just so happens that I attended a conference on civic education last week at Georgetown University. It just so happens that the ISI apparently helped fund that conference (unbeknownst to me beforehand). It just so happens that in my own talk at the conference I severely criticized the findings of the National Civic Literacy Board. I pointed out, for instance, that Stanford Professor of Education and History Sam Wineburg, in his award-winning book, Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts, and in subsequent studies had already demolished the scholarly credibility of a fact-based diagnostic as a way of teaching and understanding American history. Moreover, the premise that you are a "better" citizen and will be more "engaged" because you can identify Yorktown as the battle that brought the American Revolution to an end is just silly.

After my talk, a tall gentleman came up to me and introduced himself: Lt. General Josiah Bunting III, President of the National Civic Literacy Board. Oops! He was eminently gracious, I must say. We exchanged a few polite words. And then I heard him deliver his own address to a lunchtime audience. Most of it was about the virtues of a proper university education, all very above board. But toward the end of his remarks Lt. General Bunting showed more of his own cards. He lamented the presence of so many liberal faculty members in U.S. colleges and universities today, and he concluded his talk thus: "This must change."

I did some Googling. Turns out that the National Civic Literacy Board isn't so national after all. It is simply stacked with conservatives. The directors, besides Lt. General Bunting, include a former Reagan administration official, a former George W. Bush administration official, and a retired Rear Admiral who was Director of Naval Intelligence. Board members include U.S. Senator George Allen; the CEO of the Philip M. McKenna Foundation; the CEO of the National Association of Manufacturers; a Senior Fellow from the Hoover Institution; Roger Kimball, Editor of the New Criterion; Robert George, Director of the Madison Program at Princeton; a former Secretary of the Army; a Wall Street Journal Editorial Board member; a retired Vice Admiral in the Navy; an American Enterprise Institute scholar; a former CEO of Household Finance Corporation; and Lewis Lehrman of the Lehrman Institute; and so on. Does the mission of investigating civic literacy really require such a one-sided, unrepresentative, and so obviously politicized panel?

Conservatives are jumping all over the report with glee, and you can bet that they will press hard for the Board's recommendation that these colleges need to be held "accountable" for the way they contribute to the "civic life" of America, or not.

After I started to realize what was going on at the conference, namely that some folks in attendance saw "civic education" as a proxy and euphemistic front for a conservative agenda, I approached Lt. General Bunting with another line of inquiry. I pointed out to him that I, too, sometimes give my own students a pop quiz on American civics and American civic values, but my questions aren't about the particularities of the Civil War or Keynesian economics. Instead, I ask the following:

How many of you believe in constitutional government? How many of you believe in the rule of law? How many of you believe in checks and balances and the separation of powers among different branches of government? How many of you believe in due process? How many of you believe in trial by jury? How many of you believe in contested elections? How many of you believe in a bill of rights that protects freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, etc.? How many of you believe in universal adult suffrage? How many of you believe in the basic equality of all humans, as opposed to a caste system or a system of inherited privileges? How many of you believe that sovereignty resides in the consent of the governed? How many of you believe in democracy, rather than monarchy or aristocracy or dictatorship?

Remarkably in my experience, I've found that my students understand those questions very well and are in lock-step unanimity in endorsing those civic values. They're not the civic dummies that the National Literacy Board is trying to make them out to be.

I heard at the conference several conservative commentators bemoaning the alleged fact many liberal academics refuse to assert the "moral superiority" of the American government over other governments. What I hear in those words is something ominous: the search for an unassailable American patriotism and therewith, the search for a blanket justification for war; and also as part of that campaign, a rearguard search for scapegoats for the current national malaise in our present wartime fiasco--to be attributed no longer to the "liberal media" or to "liberal politicians" or to "liberal judges" but now to "the liberal professoriate." Holding institutions "accountable" will mean promoting American civic virtues as these conservatives define those virtues, while silencing dissenters by other means.

Why didn't the National Civic Literacy Board simply call itself the new Un-American Activities Committee? Wouldn't that have been the more forthright and honest name?

Why won't mainstream media outlets conduct even a modicum of research to inform readers and viewers about the not-so-hidden agenda behind a report such as this, instead of merely reciting uncritically the Board's findings and recommendations? Shouldn't there be some civic education about the American founders' views about the importance of a vigilant Fourth Estate?

Monday, October 23, 2006

Three Arguments for the Value of Educational Foundations

Craig Cunningham made this nice point in the comments thread of my original posting. So I thought this deserved its own post and thread. I want to argue (this argument is based on my introductory essay for a theme issue I edited) that the foundations field can be defended in educator preparation in three distinctive ways: the “liberal arts answer,” the “cultural competence answer,” and the “teacher retention answer.”

The “Liberal Arts” answer is that teaching is a complex practice, part science and part art, that requires our students to think carefully and critically about socially consequential, culturally saturated, politically volatile, and existentially defining issues within the sphere of education. The goal, here using Dewey’s terminology on freedom, is to enlarge our range of actions and thoughts. The “Liberal Arts” answer, much like the liberal arts themselves in higher education, is about fostering productive habits of mind—rigorous attention to detail, critical questioning of assumptions, respect for good data, and logical arguments—through engaging specific educational issues. Eric Bredo has nicely articulated this as avoiding errors of conceptualization. The “Cultural Competence” answer (and the one most referred to by educational policy documents) is that future educators must gain cultural competence. This answer references the “demographic imperative”: the ever growing diversity of the U.S. population; the racial and ethnic gap between youth and an overwhelmingly white teaching force; and the stark and persistent economic, social, and educational gaps between dominant and nondominant youth. The “Teacher Retention” answer indexes the “crisis” rhetoric in educational policy concerning forthcoming teacher shortages. Yet recent research by Richard Ingersoll and others has shown that teacher attrition, rather than teacher recruitment, is at the heart of contemporary teacher shortages. Over 200,000 teachers a year permanently leave the classroom. The attrition rate is much higher in poor schools than in wealthier ones and among new teachers compared to veteran teachers. In fact, almost 50% of new teachers leave within their first five years; recent data by ACORN has shown that in some urban schools the one-year attrition rate can be as high as 40%. While a host of reasons account for such turnover (retirement, job dissatisfaction, other career options, etc.), Ingersoll has argued that fundamentally, “school staffing problems are rooted in the way schools are organized and the way the teaching occupation is treated.” Teachers leave because they must deal with substantial paperwork, large teaching workloads, and sole responsibility for student misbehavior and discipline in return for average remuneration and with minimal decision-making influence. Such a structural setup of immense responsibility with little authority is prime fodder for teacher burnout. This is especially true in challenging work environments associated with poorer-resourced schools and populated by nondominant youth. Put otherwise, new teachers are not prepared for the bureaucratic and organizational features of an institution charged with the socialization and stratification of 90% of America’s youth. Such features include, among others, the isolation of teachers, the pervasiveness of a hidden curriculum of conformity, the loose coupling of decision making, the contradictory practices of conflicting goals, and the dominance of a calcified grammar of schooling. Because new teachers do not “get it” they invariably blame themselves or their students when things go awry. These are all issues that social foundations can and does address.

I do not claim that these three answers are unique or definitive. They have been articulated in a multitude of ways with myriad permutations. My goal here has simply been to develop a typology of these permutations that speak to and in the policy language games currently in play. It is to suggest that there are clear and concise arguments for why foundations has a role to play in educator preparation.

Three Arguments for the Value of Educational Foundations

Craig Cunningham made this nice point in the comments thread of my original posting. So I thought this deserved its own post and thread. I want to argue (this argument is based on my introductory essay for a theme issue I edited) that the foundations field can be defended in educator preparation in three distinctive ways: the “liberal arts answer,” the “cultural competence answer,” and the “teacher retention answer.”

The “Liberal Arts” answer is that teaching is a complex practice, part science and part art, that requires our students to think carefully and critically about socially consequential, culturally saturated, politically volatile, and existentially defining issues within the sphere of education. The goal, here using Dewey’s terminology on freedom, is to enlarge our range of actions and thoughts. The “Liberal Arts” answer, much like the liberal arts themselves in higher education, is about fostering productive habits of mind—rigorous attention to detail, critical questioning of assumptions, respect for good data, and logical arguments—through engaging specific educational issues. Eric Bredo has nicely articulated this as avoiding errors of conceptualization. The “Cultural Competence” answer (and the one most referred to by educational policy documents) is that future educators must gain cultural competence. This answer references the “demographic imperative”: the ever growing diversity of the U.S. population; the racial and ethnic gap between youth and an overwhelmingly white teaching force; and the stark and persistent economic, social, and educational gaps between dominant and nondominant youth. The “Teacher Retention” answer indexes the “crisis” rhetoric in educational policy concerning forthcoming teacher shortages. Yet recent research by Richard Ingersoll and others has shown that teacher attrition, rather than teacher recruitment, is at the heart of contemporary teacher shortages. Over 200,000 teachers a year permanently leave the classroom. The attrition rate is much higher in poor schools than in wealthier ones and among new teachers compared to veteran teachers. In fact, almost 50% of new teachers leave within their first five years; recent data by ACORN has shown that in some urban schools the one-year attrition rate can be as high as 40%. While a host of reasons account for such turnover (retirement, job dissatisfaction, other career options, etc.), Ingersoll has argued that fundamentally, “school staffing problems are rooted in the way schools are organized and the way the teaching occupation is treated.” Teachers leave because they must deal with substantial paperwork, large teaching workloads, and sole responsibility for student misbehavior and discipline in return for average remuneration and with minimal decision-making influence. Such a structural setup of immense responsibility with little authority is prime fodder for teacher burnout. This is especially true in challenging work environments associated with poorer-resourced schools and populated by nondominant youth. Put otherwise, new teachers are not prepared for the bureaucratic and organizational features of an institution charged with the socialization and stratification of 90% of America’s youth. Such features include, among others, the isolation of teachers, the pervasiveness of a hidden curriculum of conformity, the loose coupling of decision making, the contradictory practices of conflicting goals, and the dominance of a calcified grammar of schooling. Because new teachers do not “get it” they invariably blame themselves or their students when things go awry. These are all issues that social foundations can and does address.

I do not claim that these three answers are unique or definitive. They have been articulated in a multitude of ways with myriad permutations. My goal here has simply been to develop a typology of these permutations that speak to and in the policy language games currently in play. It is to suggest that there are clear and concise arguments for why foundations has a role to play in educator preparation.

Sunday, October 22, 2006

Arm teachers?

The good news is that most critics recognize the futility -- and sheer lunacy -- of Lasee's suggestion. The bad news is that the critics have turned their time and attention to Lasee and away from the thoughtfulness required.

Arm teachers?

The good news is that most critics recognize the futility -- and sheer lunacy -- of Lasee's suggestion. The bad news is that the critics have turned their time and attention to Lasee and away from the thoughtfulness required.

On standards, the curriculum, and acorns

One of my frustrations with some types of education policy writing is its irritatingly acontextual nature, as if nothing but that era (usually This Era) and the conceptualization in use at the time (i.e., a particular buzzword) is relevant for the question at hand. The writing that frustrates me can often be very detailed, accurate, and descriptive, but in a flat, largely uninteresting way. Make connections! one part of my mind screams as I plod through the piece. But, inevitably, the only connections made are to last year, or to nearby states, and only with regard to the buzzword in focus at the time. And given the speed with which we plow through buzzwords (is that a mixed metaphor?), maybe we need to keep away from narrow definitions.

The standards movement is one of those buzzwords that is a particular magnet for acontextual writing. Writing that assumes meaningful curriculum development didn't exist before the late 1980s makes me want to pull my hair out. There are multiple problems with the term standards movement, including the elision of different types of expectations (the purpose of schools with our expectations of student performance) and the elision of two separate developments in the late 1980s and early 1990s (performance assessment commonly associated with the New Standards Project and Laura Resnick, on the one hand, with efforts to create state or national curricula, on the other).

But the greater problem with most writing on standards is a failure both to look at curriculum history broadly conceived and also to think comparatively, with the U.S. as one of many countries with curriculum policy. Advocates of standards often talk about the need for alignment: we test what we say we expect from students, which should have something to do with what we plan for them to learn. Curriculum-studies folks would point out that this is parallel to their observations for many decades that there are different levels of curriculum. Terms such as the formal curriculum, the taught curriculum, and the tested curriculum abound in curriculum writings, and essentially the argument for alignment is that the formal, tested, and taught curriculum should be identical. Alignment is really about aligning different types or levels of curriculum. In abstract, that's fine as far as it goes, but alignment doesn't guarantee that the learned curriculum will be the same, nor that alignment will eliminate the hidden curriculum.

The ahistorical nature of most writing on the standards movement is more problematic. It is true that the early 1990s was the first time when we could witness most states trying to write formal curriculum expectations across a range of academic subjects. But states have written expectations before into specific parts of the curriculum, and somehow advocates for aligning different curriculum levels haven't been interested in looking at that history. The narrow definition of alignment also assumes that those who have gone before and only focused on one type of curriculum (say, the tested curriculum if you look at minimum competency testing) didn't know what they were doing in terms of its effects. And I suspect that's baloney: Even if a particular effort only targeted one chain in the desired link from expectations to what happens in student minds, advocates often have had a very clear idea of what they hoped would happen. Connecticut common-school advocate Henry Barnard, for example, hoped that blindly-graded admissions testing to high schools would drive the curriculum in grammar schools, even when only a small minority attended high schools at the time. We cannot clearly identify what is truly new in the last 15-20 years of curriculum (including the standards movement, for want of a better term) unless we look at the history with more than very narrowly-defined questions.

So, too, with international perspectives. Advocates of standards and alignment occasionally will refer to the existence of a national curriculum in other countries, most famously France, but it is not true that every other industrialized country has a long history of a centralized curriculum. I am not a comparativist, but I have a sneaky suspicion that parents have often thought that parts of the French national curriculum are compartmentalized drivel, but that's less important than a little bit of skepticism we need about the inevitability of centralized curriculum. (We can talk about de Tocqueville's model of history later.) For decades, West Germany had a clearly-articulated lack of national curriculum in reaction to the national curriculum of the Nazis. My understanding is that when Sweden's public sphere was attacked as inefficient in the 1970s and 1980s, one of the consequences was devolution of curriculum planning. After the end of apartheid, South Africans (of all ethnic and racial groups) started looking at its prior national curriculum with considerable shame. Looking internationally, I don't get the sense that the U.S. is out of step with some universal consensus on curriculum centralization.

In fact, as my astute spouse has pointed out to me on occasion, we have a nationalized curriculum in the oddest places. One of the cultural norms of elementary schools in the U.S. is to teach about the calendar. We want young children to get a sense of time, and one way to help them understand the concept of a year is to talk about seasons. But the way we do so, in all parts of the country, is tied to temperate parts of the country. In southern California and Florida, kids learn about temperate climates--that leaves turn colors in fall, that it snows in winter, and so forth. In Florida??? Leaves don't turn colors in the fall here, and deciduous trees often drop their leaves in February (especially oaks). In Florida, fall is the time of year when acorns fall, and when it gets a bit drier and more comfortable after Halloween. And don't even talk to me about teaching kids about snow. But you'll see plastic colored maple leaves in Florida classrooms this time of year. I remember the same growing up in southern California, and I suspect it's also the same in many Hawaii, Arizona, and New Mexico classrooms. We don't follow Noah Webster's exhortations to speak with the same accent, but we have the same plastic maple leaves everywhere!

Right now, I'm in the middle of writing a passage where I'm trying to flesh this idea out and realized I needed to head to the curriculum-studies and comparative-ed literature. But, as inevitably happens, the literature doesn't really answer the question I have in my head. There really isn't a comparative curriculum-studies history of the extent to which curriculum has been centralized. Darn it! So instead I get a peek at the concerns that are prominent in the literature, which forces me to think more broadly. It's a useful lacuna.

(Posted in slightly different from at my solo blog.)

On standards, the curriculum, and acorns

One of my frustrations with some types of education policy writing is its irritatingly acontextual nature, as if nothing but that era (usually This Era) and the conceptualization in use at the time (i.e., a particular buzzword) is relevant for the question at hand. The writing that frustrates me can often be very detailed, accurate, and descriptive, but in a flat, largely uninteresting way. Make connections! one part of my mind screams as I plod through the piece. But, inevitably, the only connections made are to last year, or to nearby states, and only with regard to the buzzword in focus at the time. And given the speed with which we plow through buzzwords (is that a mixed metaphor?), maybe we need to keep away from narrow definitions.

The standards movement is one of those buzzwords that is a particular magnet for acontextual writing. Writing that assumes meaningful curriculum development didn't exist before the late 1980s makes me want to pull my hair out. There are multiple problems with the term standards movement, including the elision of different types of expectations (the purpose of schools with our expectations of student performance) and the elision of two separate developments in the late 1980s and early 1990s (performance assessment commonly associated with the New Standards Project and Laura Resnick, on the one hand, with efforts to create state or national curricula, on the other).

But the greater problem with most writing on standards is a failure both to look at curriculum history broadly conceived and also to think comparatively, with the U.S. as one of many countries with curriculum policy. Advocates of standards often talk about the need for alignment: we test what we say we expect from students, which should have something to do with what we plan for them to learn. Curriculum-studies folks would point out that this is parallel to their observations for many decades that there are different levels of curriculum. Terms such as the formal curriculum, the taught curriculum, and the tested curriculum abound in curriculum writings, and essentially the argument for alignment is that the formal, tested, and taught curriculum should be identical. Alignment is really about aligning different types or levels of curriculum. In abstract, that's fine as far as it goes, but alignment doesn't guarantee that the learned curriculum will be the same, nor that alignment will eliminate the hidden curriculum.

The ahistorical nature of most writing on the standards movement is more problematic. It is true that the early 1990s was the first time when we could witness most states trying to write formal curriculum expectations across a range of academic subjects. But states have written expectations before into specific parts of the curriculum, and somehow advocates for aligning different curriculum levels haven't been interested in looking at that history. The narrow definition of alignment also assumes that those who have gone before and only focused on one type of curriculum (say, the tested curriculum if you look at minimum competency testing) didn't know what they were doing in terms of its effects. And I suspect that's baloney: Even if a particular effort only targeted one chain in the desired link from expectations to what happens in student minds, advocates often have had a very clear idea of what they hoped would happen. Connecticut common-school advocate Henry Barnard, for example, hoped that blindly-graded admissions testing to high schools would drive the curriculum in grammar schools, even when only a small minority attended high schools at the time. We cannot clearly identify what is truly new in the last 15-20 years of curriculum (including the standards movement, for want of a better term) unless we look at the history with more than very narrowly-defined questions.

So, too, with international perspectives. Advocates of standards and alignment occasionally will refer to the existence of a national curriculum in other countries, most famously France, but it is not true that every other industrialized country has a long history of a centralized curriculum. I am not a comparativist, but I have a sneaky suspicion that parents have often thought that parts of the French national curriculum are compartmentalized drivel, but that's less important than a little bit of skepticism we need about the inevitability of centralized curriculum. (We can talk about de Tocqueville's model of history later.) For decades, West Germany had a clearly-articulated lack of national curriculum in reaction to the national curriculum of the Nazis. My understanding is that when Sweden's public sphere was attacked as inefficient in the 1970s and 1980s, one of the consequences was devolution of curriculum planning. After the end of apartheid, South Africans (of all ethnic and racial groups) started looking at its prior national curriculum with considerable shame. Looking internationally, I don't get the sense that the U.S. is out of step with some universal consensus on curriculum centralization.

In fact, as my astute spouse has pointed out to me on occasion, we have a nationalized curriculum in the oddest places. One of the cultural norms of elementary schools in the U.S. is to teach about the calendar. We want young children to get a sense of time, and one way to help them understand the concept of a year is to talk about seasons. But the way we do so, in all parts of the country, is tied to temperate parts of the country. In southern California and Florida, kids learn about temperate climates--that leaves turn colors in fall, that it snows in winter, and so forth. In Florida??? Leaves don't turn colors in the fall here, and deciduous trees often drop their leaves in February (especially oaks). In Florida, fall is the time of year when acorns fall, and when it gets a bit drier and more comfortable after Halloween. And don't even talk to me about teaching kids about snow. But you'll see plastic colored maple leaves in Florida classrooms this time of year. I remember the same growing up in southern California, and I suspect it's also the same in many Hawaii, Arizona, and New Mexico classrooms. We don't follow Noah Webster's exhortations to speak with the same accent, but we have the same plastic maple leaves everywhere!

Right now, I'm in the middle of writing a passage where I'm trying to flesh this idea out and realized I needed to head to the curriculum-studies and comparative-ed literature. But, as inevitably happens, the literature doesn't really answer the question I have in my head. There really isn't a comparative curriculum-studies history of the extent to which curriculum has been centralized. Darn it! So instead I get a peek at the concerns that are prominent in the literature, which forces me to think more broadly. It's a useful lacuna.

(Posted in slightly different from at my solo blog.)

Friday, October 20, 2006

Unions and Charters, part 34

- Each side (often incorrectly) defines the other by views of its most extreme members;

- Moderate members from each group share many of the same ideas about good schooling, but each side thinks the other insists on something that will interfere with quality teaching;

- Even though some large urban districts have viewed chartering as a reform tool, the politics of school districts make them unlikely partners in scale-up;

- Both sides acknowledge the costs of their conflict, but few leaders are willing to take the first step; and

- Thin evidence about the work life of charter school teachers or how unionized charter schools operate exacerbates conflicting beliefs

Why We Need Thicker Textbooks

[Boston Globe] A candidate for state superintendent of schools said Thursday he wants thick used textbooks placed under every student's desk so they can use them for self-defense during school shootings.

"People might think it's kind of weird, crazy," said Republican Bill Crozier of Union City, a teacher and former Air Force security officer. "It is a practical thing; it's something you can do. It might be a way to deflect those bullets until police go there."

Crozier and a group of aides produced a 10-minute video Tuesday in which they shoot math, language and telephone books with a variety of weapons, including an AK-47 assault rifle and a 9mm pistol. The rifle bullet penetrated two books, including a calculus textbook, but the pistol bullet was stopped by a single book.

Why We Need Thicker Textbooks

[Boston Globe] A candidate for state superintendent of schools said Thursday he wants thick used textbooks placed under every student's desk so they can use them for self-defense during school shootings.

"People might think it's kind of weird, crazy," said Republican Bill Crozier of Union City, a teacher and former Air Force security officer. "It is a practical thing; it's something you can do. It might be a way to deflect those bullets until police go there."

Crozier and a group of aides produced a 10-minute video Tuesday in which they shoot math, language and telephone books with a variety of weapons, including an AK-47 assault rifle and a 9mm pistol. The rifle bullet penetrated two books, including a calculus textbook, but the pistol bullet was stopped by a single book.

Thursday, October 19, 2006

The Marginalization of Foundations

I should be clear about why I see the foundations field as relevant, particularly to educational policy issues. Simply put, context matters. It matters because education – from preschool to graduate school – is a complex and oftentimes contested terrain. Clarifying and contextualizing education fosters a clearer comprehension of and thus a stronger commitment to the connections between educational theory and practice. This, in turn, strengthens how we teach and learn and how we think about (and thus legislate) the teaching and learning process in K-12 and postsecondary education.

In later postings I want to explore the structural, cultural, and political issues surrounding this fragmentation. But for now I just want to draw attention to it. While AESA is the seemingly primary and intuitive organization for such an umbrella group (and historically it was founded exactly for this purpose), today scholars will much more intuitively align themselves with the sociology of education section of ASA or with the Critical Educators for Social Justice AERA SIG than with AESA. The implications are huge. On a pragmatic level, our fragmentation threatens the very survival of the foundations field. The inability to have a voice at the policy table has allowed departments of education, schools of education, colleges, and legislatures to literally take foundations out of the sequence of educator preparation. I know of far too many colleagues who have spoken about this occurring in their departments and in the states where they work. Moreover, and worsening this fate, the lack of a unified voice does not allow for foundations scholars to put forward an argument for why foundations matters for future teachers, principals and superintendents. It is easy to malign a course or an idea with very little “value-added’ to students’ standardized test scores. If foundations is not taken as a course by future educators and if its’ ideas are not codified in policy documents, it on many levels does not exist.

The Marginalization of Foundations

I should be clear about why I see the foundations field as relevant, particularly to educational policy issues. Simply put, context matters. It matters because education – from preschool to graduate school – is a complex and oftentimes contested terrain. Clarifying and contextualizing education fosters a clearer comprehension of and thus a stronger commitment to the connections between educational theory and practice. This, in turn, strengthens how we teach and learn and how we think about (and thus legislate) the teaching and learning process in K-12 and postsecondary education.

In later postings I want to explore the structural, cultural, and political issues surrounding this fragmentation. But for now I just want to draw attention to it. While AESA is the seemingly primary and intuitive organization for such an umbrella group (and historically it was founded exactly for this purpose), today scholars will much more intuitively align themselves with the sociology of education section of ASA or with the Critical Educators for Social Justice AERA SIG than with AESA. The implications are huge. On a pragmatic level, our fragmentation threatens the very survival of the foundations field. The inability to have a voice at the policy table has allowed departments of education, schools of education, colleges, and legislatures to literally take foundations out of the sequence of educator preparation. I know of far too many colleagues who have spoken about this occurring in their departments and in the states where they work. Moreover, and worsening this fate, the lack of a unified voice does not allow for foundations scholars to put forward an argument for why foundations matters for future teachers, principals and superintendents. It is easy to malign a course or an idea with very little “value-added’ to students’ standardized test scores. If foundations is not taken as a course by future educators and if its’ ideas are not codified in policy documents, it on many levels does not exist.

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

Noteworthy

The Notebook reports that privatization has not had the effect the Philadelphia School Reform Commission intended when it handed the keys to the worst-performing schools over to a handful of private organizations ranging from for-profit (i.e. Edison) to universities:

This summer’s announcement of 2006 results on the PSSA exam and of whether schools met their performance targets for adequate yearly progress reinforced a prior trend. As measured by test scores, the gap is widening between most District schools and the low-performing schools singled out for reform in 2002 that are now under private management.The percentage of students scoring proficient or better on both reading and math is now 19 points lower in the privately managed schools than the rest of the District’s schools, compared to 16 points in 2002 (see test score gains).

Implications for New York and this story: Bloomy should be keeping a close eye on Philly. It makes total sense, when you think about the mayor as the very model of a modern neoliberal, that he would want to centralize control over schools and then use that control to hand the keys to private companies. But New Yorkers are very savvy about numbers. Will they be as patient as Philadelphians with private companies who don't perform as promised?

Heckuva job, Brownie

Legitimate critique of high-stakes testing? Or a bunch of over-involved parents upset about their kids' not succeeding on a test item? You be the judge.

Something to consider: the 8th graders I work with (among whom the very best readers, admittedly, are not reading at grade level) probably could not answer this question. Analyzing character change over time is something they are only now beginning to study.

Eugenic Ideology, Past and Present

In America, ideology, memory, and history reflect a deeply embedded racialized scientism, the reverberations of which are visible in all kinds of social institutions from medicine and criminal justice, to labor policy and, of course, education. Meaningful debate regarding the translation of ideologies from the past, specifically eugenic ideology, into current debates concerning educational standards, disability and civil rights, ability testing, and class inequity is challenging for a number of reasons. First, positivistic proscriptions in an era that demands ‘evidence’ based research leave little room for qualitative or intuitive understandings. Second, if we consider the seductive ability of ideology to objectify moral sentiment and motivate action, along with the extent to which ideology defines the structures through which individuals understand the world, it becomes apparent that fear of our own complicity may play a role as well. Third, a Puritan inspired form of social discourse casts our participation in such a dialogue as a competitive bid to convince others that what we believe is right, rather than as a process of exploration and discovery. Discourse of the latter type provides an opportunity for reinterpretation of deeply embedded collective memory whereas the former reinforces the hidden elements of the boundaries of our thinking.

During the first half of the twentieth century, eugenic ideology provided imperatives and proscriptions which governed public conceptions of race, class, and gender, and spawned deep commitment among followers. Class, race, gender and status politics are still part of the discourse, but the argument is really about the interpretation of reality, rooted not only in past/present time dimensions, but also in inherent contradictions within social systems (Bodnar 1992). Schooling everywhere has long been a site of enactment for these interpretations, dictated by whomever holds power. Due, in part, to the function of collective memory, this insidious eugenic and social engineering discourse was advanced on a number of fronts throughout the twentieth century, resulting in a national dialogue about intelligence, ability, and degeneracy that has been largely defined by racialized scientism. Clearly then, effective rebuttal to the current climate will require an integrated effort.

Within schools, we remain mired in a rut that was laid long ago while recent initiatives from the right serve to solidify, rather than break down, ideological form and function. Sorting, testing, tracking, ‘gifted’ and vocational education, international test score comparisons, financial inequity, non-English speaking students, vouchers, privatization, ‘at risk’ students, and new forms of ‘apartheid schooling,’ characterize the national dialogue about schooling today. So, how far have we come? Bashing public education has always been something of a national pastime, but to criticize the 2001 reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act positions one as a person who advocates ‘leaving children behind’ or, perhaps, one who does not wish to be ‘accountable’ to the American public. I am interested in examining the ideological roots of governmental uses of eugenically rooted ideology to impose what Nancy Ordover (2003) refers to as the ‘technofix’ on the underclass.

Examples abound of the ability of the purveyors of official culture to divert attention from meaningful correctives across a broad spectrum of social policy at the same time as they fortify the economic and political context in which inequity thrives. And so we find ourselves, fifty-two years after the Brown v. Board of Education decision in a state of what Kozol (2005) has called apartheid schooling. If, as Grumet (1988) observed, school curriculum is best defined as what the older generation chooses to tell the younger, then it becomes the task of schools to dictate not only what we remember of the past, but what we believe about the present and hope for the future. Ideology is insidious, but it can also be transformative – I hope to contribute to an autobiographical national dialogue that can get us there.

Bodnar, J. (1992). Remaking America: Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press.

Grumet, M. (1988). Bitter Milk: Women and Teaching. Amherst, University of Massachusetts Press.

Kozol, J. (2005). The Shame of the Nation: The Restoration of Apartheid Schooling in America. New York, Crown.

Ordover, N. (2003). American eugenics: race, queer anatomy, and the science of nationalism. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

Eugenic Ideology, Past and Present

In America, ideology, memory, and history reflect a deeply embedded racialized scientism, the reverberations of which are visible in all kinds of social institutions from medicine and criminal justice, to labor policy and, of course, education. Meaningful debate regarding the translation of ideologies from the past, specifically eugenic ideology, into current debates concerning educational standards, disability and civil rights, ability testing, and class inequity is challenging for a number of reasons. First, positivistic proscriptions in an era that demands ‘evidence’ based research leave little room for qualitative or intuitive understandings. Second, if we consider the seductive ability of ideology to objectify moral sentiment and motivate action, along with the extent to which ideology defines the structures through which individuals understand the world, it becomes apparent that fear of our own complicity may play a role as well. Third, a Puritan inspired form of social discourse casts our participation in such a dialogue as a competitive bid to convince others that what we believe is right, rather than as a process of exploration and discovery. Discourse of the latter type provides an opportunity for reinterpretation of deeply embedded collective memory whereas the former reinforces the hidden elements of the boundaries of our thinking.

During the first half of the twentieth century, eugenic ideology provided imperatives and proscriptions which governed public conceptions of race, class, and gender, and spawned deep commitment among followers. Class, race, gender and status politics are still part of the discourse, but the argument is really about the interpretation of reality, rooted not only in past/present time dimensions, but also in inherent contradictions within social systems (Bodnar 1992). Schooling everywhere has long been a site of enactment for these interpretations, dictated by whomever holds power. Due, in part, to the function of collective memory, this insidious eugenic and social engineering discourse was advanced on a number of fronts throughout the twentieth century, resulting in a national dialogue about intelligence, ability, and degeneracy that has been largely defined by racialized scientism. Clearly then, effective rebuttal to the current climate will require an integrated effort.

Within schools, we remain mired in a rut that was laid long ago while recent initiatives from the right serve to solidify, rather than break down, ideological form and function. Sorting, testing, tracking, ‘gifted’ and vocational education, international test score comparisons, financial inequity, non-English speaking students, vouchers, privatization, ‘at risk’ students, and new forms of ‘apartheid schooling,’ characterize the national dialogue about schooling today. So, how far have we come? Bashing public education has always been something of a national pastime, but to criticize the 2001 reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act positions one as a person who advocates ‘leaving children behind’ or, perhaps, one who does not wish to be ‘accountable’ to the American public. I am interested in examining the ideological roots of governmental uses of eugenically rooted ideology to impose what Nancy Ordover (2003) refers to as the ‘technofix’ on the underclass.

Examples abound of the ability of the purveyors of official culture to divert attention from meaningful correctives across a broad spectrum of social policy at the same time as they fortify the economic and political context in which inequity thrives. And so we find ourselves, fifty-two years after the Brown v. Board of Education decision in a state of what Kozol (2005) has called apartheid schooling. If, as Grumet (1988) observed, school curriculum is best defined as what the older generation chooses to tell the younger, then it becomes the task of schools to dictate not only what we remember of the past, but what we believe about the present and hope for the future. Ideology is insidious, but it can also be transformative – I hope to contribute to an autobiographical national dialogue that can get us there.

Bodnar, J. (1992). Remaking America: Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press.

Grumet, M. (1988). Bitter Milk: Women and Teaching. Amherst, University of Massachusetts Press.

Kozol, J. (2005). The Shame of the Nation: The Restoration of Apartheid Schooling in America. New York, Crown.

Ordover, N. (2003). American eugenics: race, queer anatomy, and the science of nationalism. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

Musing about safe schools

Not surprisingly, policymakers are poised to step in and fix the problem. In a rush to “give an illusion that things will be safer” (as Dewey Cornell at the University of Virginia put it in this week’s Education Week), policymakers offer the things they have at their disposal: statewide regulation and money for security systems. Schools will lock doors, hire security officers, install radios, train staff, and monitor all entrances.

It is not clear that these measures are needed or that they will help. UVA Professor Cornell reminds us that this kind of horrific violence remains extremely rare, that a school might experience something like this once every 12,000 years. Does it make sense to take extreme precautions that impede open access to schools? And will turning schools into maximum-security-institutions-in-reverse have the desired effect? Will it prevent school shootings? As Ed Week (October 11, 2006) reports, the student who shot and killed six classmates in Pearl (Mississippi) High School in 1997 later told investigators that a locked door or a metal detector would not have stopped him. In a 2005 student shooting at Red Lake Indian Reservation in Minnesota, the first person to get shot was the school security officer.

While significant attention is being paid to violence in schools, there are some aspects of the school shootings that are not getting enough scrutiny. Consider (as Bob Herbert does in Sunday’s New York Times) that shooters are nearly always white males, adolescent or adult, typically students rather than intruders. Their hostages and targets are typically girls or young women. Misogyny, it seems, is alive and well. School shootings are high profile ways the way to dramatize sex-based resentment. This is not a simple problem to be solved but a function of human relations in our broader society. How do we even think about a response that is nuanced and sensitive enough to address this deeper issue?

What does it mean to prevent school violence? What will it take?

It will mean paying careful, thoughtful attention to what we do know about how and why a human being will go to a school intent on using a gun (that it’s targeted rather than impulsive, that others often know of the attacker’s plans, that the attacker feels bullied or disrespected, that the attacker has struggled with loss, that the attacker has access to weapons). These observations come from a National Threat Assessment Center report and are listed in Ed Week. It also means admitting what we don’t – and perhaps can’t --know (that the shooters present no profile useful in distinguishing them from the rest of the population and that they rarely make prior threats).

It may well mean looking for inspiration in unlikely places and accepting models that counter our immediate intuitions about how to respond. Much has been made of the Amish response to last week’s shootings. The very first reports of violence in this non-violent community were accompanied by the word that the families of the dead and injured forgave the man responsible. Perhaps our first response to violence should be opening rather than closing the doors of hearts and schools.

But practically speaking, what would this look like? Even the Amish who stunned the world with their offer of forgiveness – and who typically divorce themselves from “English” living around them -- have turned to outside consultants to train teachers in an emergency, and – to the surprise of experts – are considering “arming” those teachers with cell phones.

I do not write here to specify action but to remind all of a dangerous tendency in our thinking. We rush to fix the problem we can fix readily without engaging in what Dewey famously called “the method of intelligence.” We short-circuit the moments of interpreting, of formulating possible courses of action, and anticipating the consequences of potential responses. By doing that, we fail to recognize the problem. We let the do-able define the problem; we don’t take the time to let the problem reveal itself.

Sometimes it helps to focus on concrete examples when we are trying to navigate the shoals of immediacy and thoughtfulness, of the urgent “real” and the interesting but less immediate “ideal,” of the compelling desire to lock-down and the belief that an open and forgiving heart is the only path to ending violence. I can offer one such example among schools that have instituted partnerships with local police in a thoughtfully planned effort to prevent all kinds of trouble. Penn Manor High School (Millersville, PA) now proudly claims as a de facto staff member a local township police officer. Jason Hottenstein is listed on the Administrative website as a “school resource officer.” He reports to work at the high school every day though he remains an officer in good standing on the police force. (School district and municipality contribute equally to his compensation.)

Officer Hottenstein rarely appears in uniform, but he is a constant presence. He is part security guard, part counselor, part legal advisor, part “bad cop,” part “good cop,” part trouble-shooter -- but wholly an adult staff member who understands that security involves relationships with students over time. His presence in the building is a constant reminder – to students and staff -- that security involves the entire community.

Not every police officer could manage what this intelligent, caring man does. But that does not mean that other schools should not look carefully at the example set here. This partnership between school and municipality, between educator and office, is a crystal clear example of a district that has taken issues of security seriously without sacrificing the attention to relation that makes security meaningful.

Musing about safe schools

Not surprisingly, policymakers are poised to step in and fix the problem. In a rush to “give an illusion that things will be safer” (as Dewey Cornell at the University of Virginia put it in this week’s Education Week), policymakers offer the things they have at their disposal: statewide regulation and money for security systems. Schools will lock doors, hire security officers, install radios, train staff, and monitor all entrances.

It is not clear that these measures are needed or that they will help. UVA Professor Cornell reminds us that this kind of horrific violence remains extremely rare, that a school might experience something like this once every 12,000 years. Does it make sense to take extreme precautions that impede open access to schools? And will turning schools into maximum-security-institutions-in-reverse have the desired effect? Will it prevent school shootings? As Ed Week (October 11, 2006) reports, the student who shot and killed six classmates in Pearl (Mississippi) High School in 1997 later told investigators that a locked door or a metal detector would not have stopped him. In a 2005 student shooting at Red Lake Indian Reservation in Minnesota, the first person to get shot was the school security officer.

While significant attention is being paid to violence in schools, there are some aspects of the school shootings that are not getting enough scrutiny. Consider (as Bob Herbert does in Sunday’s New York Times) that shooters are nearly always white males, adolescent or adult, typically students rather than intruders. Their hostages and targets are typically girls or young women. Misogyny, it seems, is alive and well. School shootings are high profile ways the way to dramatize sex-based resentment. This is not a simple problem to be solved but a function of human relations in our broader society. How do we even think about a response that is nuanced and sensitive enough to address this deeper issue?

What does it mean to prevent school violence? What will it take?

It will mean paying careful, thoughtful attention to what we do know about how and why a human being will go to a school intent on using a gun (that it’s targeted rather than impulsive, that others often know of the attacker’s plans, that the attacker feels bullied or disrespected, that the attacker has struggled with loss, that the attacker has access to weapons). These observations come from a National Threat Assessment Center report and are listed in Ed Week. It also means admitting what we don’t – and perhaps can’t --know (that the shooters present no profile useful in distinguishing them from the rest of the population and that they rarely make prior threats).

It may well mean looking for inspiration in unlikely places and accepting models that counter our immediate intuitions about how to respond. Much has been made of the Amish response to last week’s shootings. The very first reports of violence in this non-violent community were accompanied by the word that the families of the dead and injured forgave the man responsible. Perhaps our first response to violence should be opening rather than closing the doors of hearts and schools.

But practically speaking, what would this look like? Even the Amish who stunned the world with their offer of forgiveness – and who typically divorce themselves from “English” living around them -- have turned to outside consultants to train teachers in an emergency, and – to the surprise of experts – are considering “arming” those teachers with cell phones.

I do not write here to specify action but to remind all of a dangerous tendency in our thinking. We rush to fix the problem we can fix readily without engaging in what Dewey famously called “the method of intelligence.” We short-circuit the moments of interpreting, of formulating possible courses of action, and anticipating the consequences of potential responses. By doing that, we fail to recognize the problem. We let the do-able define the problem; we don’t take the time to let the problem reveal itself.

Sometimes it helps to focus on concrete examples when we are trying to navigate the shoals of immediacy and thoughtfulness, of the urgent “real” and the interesting but less immediate “ideal,” of the compelling desire to lock-down and the belief that an open and forgiving heart is the only path to ending violence. I can offer one such example among schools that have instituted partnerships with local police in a thoughtfully planned effort to prevent all kinds of trouble. Penn Manor High School (Millersville, PA) now proudly claims as a de facto staff member a local township police officer. Jason Hottenstein is listed on the Administrative website as a “school resource officer.” He reports to work at the high school every day though he remains an officer in good standing on the police force. (School district and municipality contribute equally to his compensation.)

Officer Hottenstein rarely appears in uniform, but he is a constant presence. He is part security guard, part counselor, part legal advisor, part “bad cop,” part “good cop,” part trouble-shooter -- but wholly an adult staff member who understands that security involves relationships with students over time. His presence in the building is a constant reminder – to students and staff -- that security involves the entire community.